How Deeper Knowledge of Facial Anatomy Shapes Safer Beauty Treatments

This is a collaborative post.

This article about beauty treatments was written by a guest writer, and the experiences are theirs, not mine. Jen x

The silent foundation of aesthetics

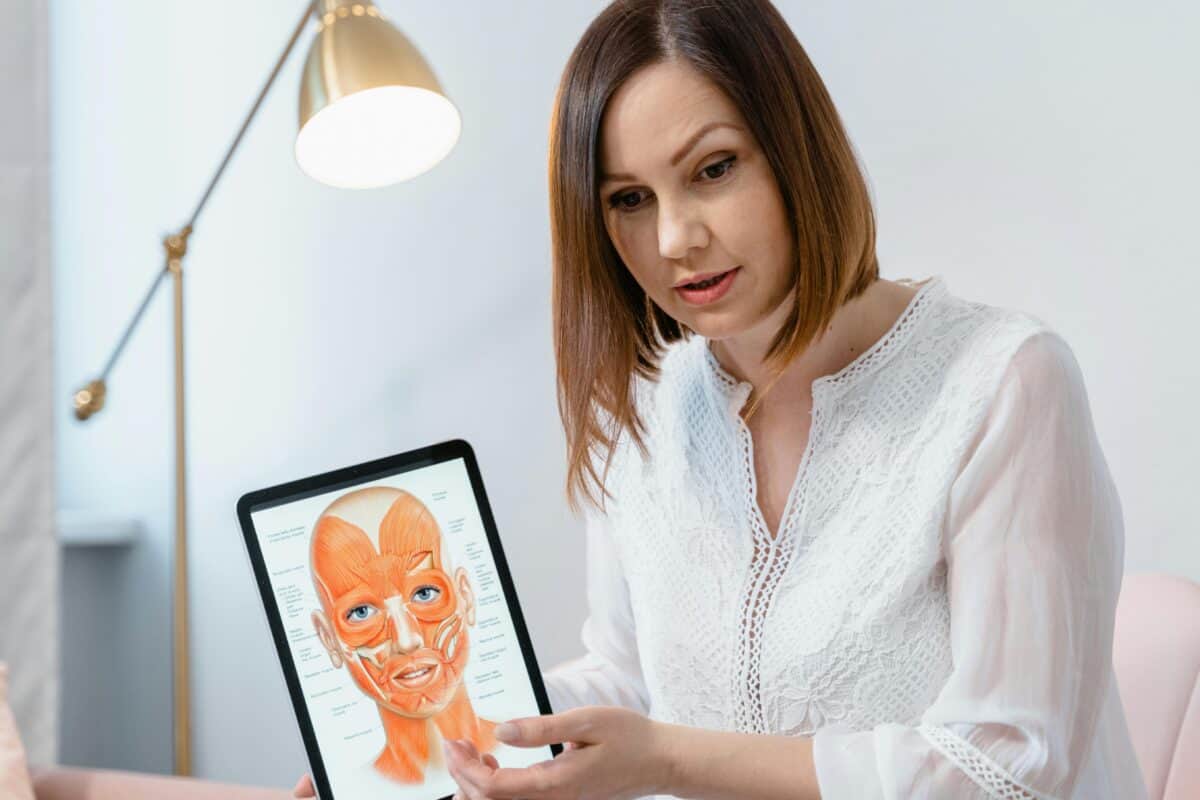

When people think about cosmetic procedures and beauty treatments, they often imagine results. A smoother forehead, a lifted jawline, maybe fuller lips. What rarely crosses their mind is the network of vessels, nerves, and fat pads that sit just beneath the skin. Yet that is exactly what determines whether a treatment is safe or risky. Beauty treatments that involve needles, threads, or energy-based devices don’t operate on the surface alone. They interact with structures that, if misjudged, can cause complications.

I’ve sat in a chair myself, nervous about what a syringe might do if it were misplaced. That moment made me realise how little patients think about the invisible layers under the skin. It’s easy to see beauty as superficial. But the truth is, the safety of a cosmetic intervention depends far more on the unseen map of the face than the product used.

Practitioners who invest time in learning facial anatomy are essentially equipping themselves with a safety net. Not only can they minimise risks, but they can also tailor treatments more accurately to the unique features of each person.

Precision through anatomy

Consider how complex the face actually is. Each region carries its own distinct challenges for beauty treatments. The temple, for instance, holds fragile vessels close to the surface. The nose is traversed by arteries that, if injected incorrectly, can cause serious issues.

Even lips, which may look straightforward, have multiple entry points where an accidental hit can lead to bruising or worse. Without detailed anatomical knowledge, treating these areas is like navigating a city without a map. You might get where you want, but the chance of a wrong turn is dangerously high.

What separates a cautious injector from a reckless one is not confidence. It is the awareness of depth, planes, and landmarks. Think of the cheeks: a filler placed too superficially can create lumps; injected too deeply, it may migrate or compress structures.

Knowing the safe zones for beauty treatments, a practitioner can adjust the angle, depth, and even the type of product used. This isn’t about memorising diagrams. It’s about translating anatomy into real-time decisions, needle in hand, patient watching closely.

Safety also links to artistry. A person might want their face balanced, not overfilled. If an injector knows where the retaining ligaments sit, they can lift areas in a way that respects the natural support of the face.

When anatomy guides technique for beauty treatments, the outcome looks more harmonious, and the treatment carries far less risk. That blend of safety and subtlety doesn’t come from instinct. It comes from structured knowledge, carefully studied and consistently applied.

Learning is a lifelong process

I’ve spoken to professionals who admitted they underestimated how much they needed to study anatomy at the start of their careers. Some thought initial training was enough, only to realise that complications often arise when anatomical variations appear.

No two faces are identical. A textbook might describe a standard path of the facial artery, but in practice, it may shift slightly, leaving one side different from the other. The only way to prepare for those differences is by continuing to study, refresh, and refine knowledge over time.

That is why many beauty treatments practitioners turn to structured education rather than relying on experience alone. One resource that stood out to me was the advanced programs offering in-depth facial anatomy insights.

These masterclasses are designed not just for beginners but for professionals who already work in the field and want to push their precision further. They combine theoretical depth with hands-on practice, often using cadaver dissections to show exactly how vessels and nerves appear in reality compared to a textbook diagram. That visual, tactile exposure is invaluable.

I see a clear difference between someone who has only trained once years ago and someone who keeps returning to courses like these. The latter tend to have a confidence that comes from preparation, not assumption. They can adapt to unexpected anatomical differences because they’ve seen variations up close. The platform also structures its learning in a way that links clinical application to safety.

It doesn’t isolate theory. Instead, it shows how each anatomical layer matters when a syringe is inserted or when a thread is placed. For me as a patient, that kind of education makes me more willing to trust. When I know a practitioner invests in programs that go into this level of depth, it reassures me that they’re taking safety as seriously as results.

What also struck me is that these beauty treatments programs don’t frame anatomy as a one-time subject to pass and move on from. They treat it as a living skill, something that grows alongside clinical practice. Every new technique, whether it’s a novel filler, a device, or an energy-based treatment, interacts with anatomy in a slightly different way. Without revisiting the basics at an advanced level, a practitioner risks falling behind. Courses that integrate cadaver training with live demonstrations provide a space to constantly refresh that foundation.

Patient confidence and future direction

When patients choose a practitioner for beauty treatments, most focus on results displayed in photos. Smooth lines, symmetry, that polished look. But safety rarely shows in a photo. It’s hidden in the absence of complications.

A bruise avoided, a vessel spared, a nerve untouched. Patients may not recognise the value of anatomical knowledge right away, but they feel its benefits when treatments heal smoothly, when they don’t leave the clinic with swelling that lasts for weeks.

For me, knowing that a practitioner prioritises anatomy has become a deciding factor. I would rather sit through a consultation where they pull out diagrams and talk about arteries than listen to vague promises of instant results.

The future of aesthetic medicine for beauty treatments seems tied not only to new products or technologies but to how seriously the field continues to invest in anatomical education. As demand grows and treatments become more sophisticated, the margin for error shrinks. The only safeguard is depth of knowledge, and the willingness of professionals to keep learning long after their initial certification.

Patients are also starting to ask different questions. Instead of only asking which product will be used, more people want to know about training, anatomy expertise, and complication management. That shift in patient awareness places even more pressure on practitioners to be prepared. Safety can no longer be taken for granted; it has to be proven through education and practice.

And when I think about my own beauty treatments, I find myself far more confident in choosing someone who invests in anatomical courses regularly. Not because I expect to quiz them on every artery, but because I know they’re doing the work behind the scenes. They’re preparing for the scenarios I can’t see, making choices that reduce risks before I even realise there was one. For patients like me, that kind of preparation makes all the difference in beauty treatments.